Pragmatism is, to a significant extent, about data.

But data, to a significant extent, is about authority.

Take the straight forward datum of the number of planets in our solar system. Many people think they know the answer is nine. And it was. But now it's eight.

And if it was nine and now it's eight, then should we be surprised to learn that it is seven or six or negative 3.5?

I can't see the planets (not all). I can't count them myself. In order to know how many there are, I must trust an authority. And if that authority changes its mind, my trust is damaged. This is as it should be.

Which types of fat lead to heart disease?

According to the American Heart Association, "Eating foods that contain saturated fats raises the level of cholesterol in your blood. High levels of LDL cholesterol in your blood increase your risk of heart disease and stroke."

In the 1930s, saturated fats were being replaced with artificial "trans" fats - solid fats made from hydrogenated vegetable oil. Hence Crisco largely replaced lard; margarine largely replaced butter. Saturated fats were seen as unhealthy and trans fats were seen as healthier.

In the mid 1990's, health authorities such as the FDA began linking trans fats to heart disease. Last Wednesday, the FDA officially banned trans fats for many commercial purposes.

And just a few months ago, an important meta-analysis of 72 different studies of saturated fat found no link to heart disease.

Then weeks later, that paper was publicly criticized for containing major errors.

This situation is confusing: Wikipedia has a page dedicated to the controversy.

So while saturated fats were once bad and trans fats were once good, the reverse may now be true (or maybe not). Hence the "pragmatic" response, from many, is to simply stop listening to anything that "nutrition authorities" claim.

Yet is that really a pragmatic response - to ignore scientific authority because it occasionally changes and even reverses factual claims?

I don't think so.

I think the key is to realize that pragmatism is about data, yes, but it is more importantly about balance and about finding optimal paths between extremes.

If one extreme is to ignore science, and the other is to blindly believe its every claim, where is the optimal path?

To answer that question we need to understand that science is most fundamentally the process of hypothesis testing.

Science is not and should not be about defining or presenting "truth". It is and should be about generating and testing more and more hypotheses.

This process of hypothesis testing is not suppose to give us truth, it is suppose to get us closer to it.

And in doing so, sometimes, it has to backtrack.

Pragmatism is not about blindly following authorities or rejecting them - it is about coming up with our own criteria for evaluations - based on track records, prior successes, honesty, integrity. These evaluations are themselves hypotheses which must be tested again and again over time.

We should not hope to find a single authority to trust blindly for all our lives. Instead we should listen to a diversity of voices and adjust our confidence in each as they variously conform and diverge with each other and with our own experiences, reason and conscience.

Jon Cracraft's Blog

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Thursday, June 18, 2015

The Pope is a Pragmatist? (post 31)

In October of 2014, Pope Francis declared that the theories of the big bang and evolution were consistent with the Catholic interpretation of God's creation of the world.

Today the Pope demanded that world leaders act swiftly to combat climate change.

In doing so I think he has come to a powerful conclusion: the only way to move forward, with a positive mindset, in this world full of pain, hatred, injustice and bitter disagreement, is to do so within a spirit of pragmatism.

Pragmatism says that it's OK to have disagreements - in fact, it's healthy. However, when it becomes imperative that certain disagreements be resolved and unified action is required - then disputes should be settled in light of the best scientific data, theories and models we have available.

This is not to say science can't be wrong. Science can be wrong. And scientists can change their minds as new evidence comes to light or new theories make sense of old data.

There is overwhelming consensus among world scientists for accepting the big bang, evolution and climate change as realities we must accept if we want to understand where we come from and how to move forward. These theories have proven their utility and predictive power time and time again. It is possible that new evidence could lead to a paradigm shift, but such a paradigm shift would have to preserve most of the mechanics and predictive power of the current theories - much as Relativity preserved most of the mechanics and predictive power of Newtonian Physics.

Today the Pope demanded that world leaders act swiftly to combat climate change.

In doing so I think he has come to a powerful conclusion: the only way to move forward, with a positive mindset, in this world full of pain, hatred, injustice and bitter disagreement, is to do so within a spirit of pragmatism.

Pragmatism says that it's OK to have disagreements - in fact, it's healthy. However, when it becomes imperative that certain disagreements be resolved and unified action is required - then disputes should be settled in light of the best scientific data, theories and models we have available.

This is not to say science can't be wrong. Science can be wrong. And scientists can change their minds as new evidence comes to light or new theories make sense of old data.

There is overwhelming consensus among world scientists for accepting the big bang, evolution and climate change as realities we must accept if we want to understand where we come from and how to move forward. These theories have proven their utility and predictive power time and time again. It is possible that new evidence could lead to a paradigm shift, but such a paradigm shift would have to preserve most of the mechanics and predictive power of the current theories - much as Relativity preserved most of the mechanics and predictive power of Newtonian Physics.

Saturday, June 6, 2015

Pragmatism in Action (post 30)

You can be a pragmatist and a Christian.

You can be a pragmatist and a Muslim.

You can be a pragmatist and a Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Jew, Pagan, Atheist, Republican, Democrat, Libertarian, etc.

The beauty of pragmatism is that it is something that can be agreed upon even by people who hold very different moral, religious or political beliefs.

And when groups of people with different beliefs find themselves fighting over public policy, pragmatism can provide a peaceful means for a solution.

For example, imagine a town where groups of Christians and atheists are fighting over a sex education program in public schools.

A pragmatist would say, OK - is there a comprehensive body of peer-reviewed research on sex education programs and their results?

If not, the pragmatist would advocate for a democratic solution where the larger group would have a greater say - while ensuring some compromises and allowances for the minority group.

If there is a body of rigorous research, then what does it say about the consequences of the different programs? If it reveals that there are certain kinds of programs that have reliably led to lower rates of teen pregnancy and STDs (which everyone agrees is positive), then both the Christians and atheists should seriously consider modifying their proposals to be more in line with the ones that have worked. If such programs contain lessons that some people find truly morally reprehensible, then a pragmatic compromise would be to allow some individuals to have their children opt out.

Pragmatism isn't complicated.

It is our best means for preventing societies from splintering apart.

You can be a pragmatist and a Muslim.

You can be a pragmatist and a Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Jew, Pagan, Atheist, Republican, Democrat, Libertarian, etc.

The beauty of pragmatism is that it is something that can be agreed upon even by people who hold very different moral, religious or political beliefs.

And when groups of people with different beliefs find themselves fighting over public policy, pragmatism can provide a peaceful means for a solution.

For example, imagine a town where groups of Christians and atheists are fighting over a sex education program in public schools.

A pragmatist would say, OK - is there a comprehensive body of peer-reviewed research on sex education programs and their results?

If not, the pragmatist would advocate for a democratic solution where the larger group would have a greater say - while ensuring some compromises and allowances for the minority group.

If there is a body of rigorous research, then what does it say about the consequences of the different programs? If it reveals that there are certain kinds of programs that have reliably led to lower rates of teen pregnancy and STDs (which everyone agrees is positive), then both the Christians and atheists should seriously consider modifying their proposals to be more in line with the ones that have worked. If such programs contain lessons that some people find truly morally reprehensible, then a pragmatic compromise would be to allow some individuals to have their children opt out.

Pragmatism isn't complicated.

It is our best means for preventing societies from splintering apart.

Saturday, May 30, 2015

The Need for Pragmatists (post 29)

All societies are hierarchical. This includes egalitarian societies. This includes anarchist societies, as well as societies that employ no coercion, make rules by consensus and don't recognize leaders. For primates, the primary means by which hierarchy is established has never been coercion - it has instead been grooming. For humans, grooming has been superseded by language. When we use language, we are engaging in the establishment of hierarchy.

At any given time one could be engaged in an effort to raise one's hierarchical rank within one's society. Also at any given time, one could be engaged in an effort to improve one's society overall (for example, by increasing the abundance of resources or increasing safety or raising the status of the society relative to other societies or by promoting a beneficial change in culture).

These pursuits need not be mutually exclusive, and in healthy society we might imagine that they largely coincide.

It makes sense that one would increase their rank within a society by doing things that are helpful for the society.

However, this is not necessarily the case. In dysfunctional societies the means for rising within the hierarchy could prove detrimental to the society as a whole.

What determines whether or not a society is healthy or dysfunctional?

The answer must be found within the worldviews, culture, beliefs and values of the individuals who make up the society.

Whenever a significant number of individuals within a society begin admiring, respecting or lauding actions and rhetoric that are detrimental to the society overall - the society takes a turn from healthy toward dysfunctional.

Disputes within a society over whether certain ideas are positive or negative can themselves either be positive or negative depending on their severity. If the disputes are handled in a civil, charitable manner, they can lead to improved culture on both sides. If they instead become bitter and entrenched, they can turn the entire society toward dysfunction. This is especially true if a primary means of gaining status within a particular faction is to work toward the detriment of rivals.

When disputes between factions become heated to the point where they threaten to be dysfunctional, it is up to the centrists, moderates and pragmatists - the peacemakers - to attempt to tone down the rhetoric and foster mutual understanding.

In the United States of America we are in desperate need of such pragmatists right now.

At any given time one could be engaged in an effort to raise one's hierarchical rank within one's society. Also at any given time, one could be engaged in an effort to improve one's society overall (for example, by increasing the abundance of resources or increasing safety or raising the status of the society relative to other societies or by promoting a beneficial change in culture).

These pursuits need not be mutually exclusive, and in healthy society we might imagine that they largely coincide.

It makes sense that one would increase their rank within a society by doing things that are helpful for the society.

However, this is not necessarily the case. In dysfunctional societies the means for rising within the hierarchy could prove detrimental to the society as a whole.

What determines whether or not a society is healthy or dysfunctional?

The answer must be found within the worldviews, culture, beliefs and values of the individuals who make up the society.

Whenever a significant number of individuals within a society begin admiring, respecting or lauding actions and rhetoric that are detrimental to the society overall - the society takes a turn from healthy toward dysfunctional.

Disputes within a society over whether certain ideas are positive or negative can themselves either be positive or negative depending on their severity. If the disputes are handled in a civil, charitable manner, they can lead to improved culture on both sides. If they instead become bitter and entrenched, they can turn the entire society toward dysfunction. This is especially true if a primary means of gaining status within a particular faction is to work toward the detriment of rivals.

When disputes between factions become heated to the point where they threaten to be dysfunctional, it is up to the centrists, moderates and pragmatists - the peacemakers - to attempt to tone down the rhetoric and foster mutual understanding.

In the United States of America we are in desperate need of such pragmatists right now.

Friday, May 29, 2015

On Society (post 28)

A society is run by its most powerful members.

In our society, power is supposed to come from a mandate of the majority, but, clearly, it can and does also come from wealth.

The most powerful members make decisions that affect our wellbeing and also their ability to retain and build more power.

Much depends on whether and to what extent those goals conflict or coincide - and that, in turn, depends largely on the worldviews, culture, beliefs and values of our society - both of the masses and of the elite.

One particular category of values/beliefs that is of primary importance concerns how a society should respond to or treat its weakest, most vulnerable and most incompetent members.

Typically members of a society with the least amount of power are thought to be children, the elderly and the sick - which should include the mentally ill. I submit that we should also include addicts (especially those who became addicted as children), the uneducated and the unloved.

Though there are myriad ways the leaders of a society can treat such people, these can be lumped into a few basic types.

What are the ideological considerations? What are the pragmatic considerations?

In our society, power is supposed to come from a mandate of the majority, but, clearly, it can and does also come from wealth.

The most powerful members make decisions that affect our wellbeing and also their ability to retain and build more power.

Much depends on whether and to what extent those goals conflict or coincide - and that, in turn, depends largely on the worldviews, culture, beliefs and values of our society - both of the masses and of the elite.

One particular category of values/beliefs that is of primary importance concerns how a society should respond to or treat its weakest, most vulnerable and most incompetent members.

Typically members of a society with the least amount of power are thought to be children, the elderly and the sick - which should include the mentally ill. I submit that we should also include addicts (especially those who became addicted as children), the uneducated and the unloved.

Though there are myriad ways the leaders of a society can treat such people, these can be lumped into a few basic types.

- Do not spend resources on them.

- Spend resources to punish them.

- Spend resources to attempt to increase their competency.

- Spend resources to feed, house and placate them.

- Spend resources to create productive roles for them.

What are the ideological considerations? What are the pragmatic considerations?

Thursday, May 28, 2015

Increase the Minimum Wage? (post 27)

Should we (meaning either Indiana or the US) raise the minimum wage?

The pragmatic approach to an answer is to carefully examine the canonical research on the topic. A sampling of such research is found below.

While conclusions from such research are ambivalent, an increasing proportion of studies are finding that the effects are generally more positive than negative. I suspect that a lot depends on the particular state of an economy when a minimum wage is raised - and how far it is raised. I have yet to find any studies that address this question directly, but I wonder whether, in contexts where capital is inexpensive, raises in minimum wages have more beneficial effects than where capital is expensive.

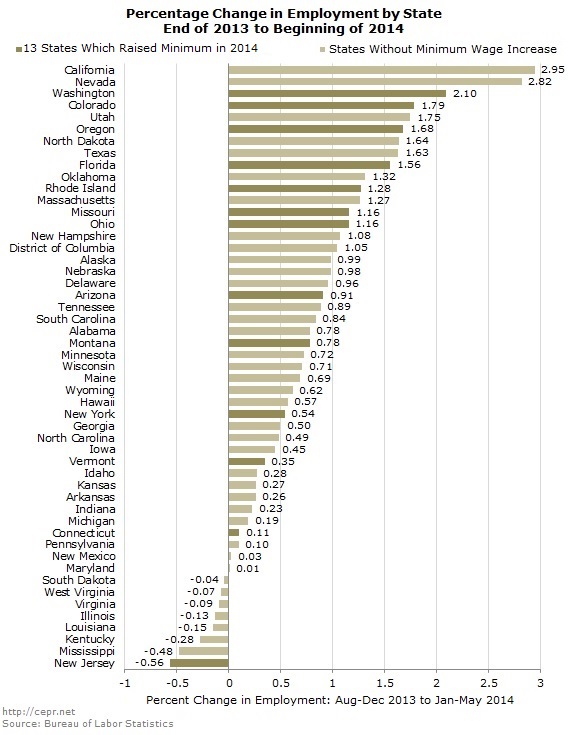

1) In a recent CEPR study of US states that raised their minimum wages in 2014:

"GS compared the employment change between December and January in the 13 states where the minimum wage increased with the changes in the remainder of the states. The GS analysis found that the states where the minimum wage went up had faster employment growth than the states where the minimum wage remained at its 2013 level."

http://www.cepr.net/blogs/cepr-blog/2014-job-creation-in-states-that-raised-the-minimum-wage

The pragmatic approach to an answer is to carefully examine the canonical research on the topic. A sampling of such research is found below.

While conclusions from such research are ambivalent, an increasing proportion of studies are finding that the effects are generally more positive than negative. I suspect that a lot depends on the particular state of an economy when a minimum wage is raised - and how far it is raised. I have yet to find any studies that address this question directly, but I wonder whether, in contexts where capital is inexpensive, raises in minimum wages have more beneficial effects than where capital is expensive.

If forced to take a stance based on what I know now, I would advocate for a modest increase in the minimum wage.

Here are some important studies and summaries for the debate:

1) In a recent CEPR study of US states that raised their minimum wages in 2014:

"GS compared the employment change between December and January in the 13 states where the minimum wage increased with the changes in the remainder of the states. The GS analysis found that the states where the minimum wage went up had faster employment growth than the states where the minimum wage remained at its 2013 level."

http://www.cepr.net/blogs/cepr-blog/2014-job-creation-in-states-that-raised-the-minimum-wage

2) In a CBO study published in Feb 2014 on the effect of raising the federal minimum wage:

3) Journalist's Resource provides an excellent summary of the most prominent research:

http://journalistsresource.org/studies/economics/inequality/the-effects-of-raising-the-minimum-wage

http://journalistsresource.org/studies/economics/inequality/the-effects-of-raising-the-minimum-wage

4) Politicfact.com, in fact checking a claim made by Ben Cardin, provides an excellent summary of different studies and concludes:

"We looked at nationwide employment data in the years following minimum wage increases since 1978, and sometimes there was job growth, and sometimes there was job loss. Modern research tends to show that raising the minimum wage has little significant impact -- positive or negative -- on employment."

"We looked at nationwide employment data in the years following minimum wage increases since 1978, and sometimes there was job growth, and sometimes there was job loss. Modern research tends to show that raising the minimum wage has little significant impact -- positive or negative -- on employment."

5) In 2010, The Institute for Research on Labor and Employment published a study which found:

"For cross-state contiguous counties, we find strong earnings

effects and no employment effects of minimum wage

increases."

6) A NBER paper from 2006 found that:

"Although the wide range of estimates is striking, the oft-stated assertion that the new minimum

wage research fails to support the traditional view that the minimum wage reduces the employment of

low-wage workers is clearly incorrect."

http://www.nber.org/papers/w12663.pdf

http://www.nber.org/papers/w12663.pdf

7) In 1998 the Economic Policy Institute published a study where:

"The principal findings are that:

* The 1996 and 1997 minimum wage increases raised the wages of almost 10 million workers. About 71% of these workers were adults and 58% were women. Just under half (46%) worked full time and another third worked 20 to 34 hours per week.

* The average minimum wage worker is responsible for providing more than half (54%) of his or her family’s weekly earnings.

* The two-stage increase disproportionately benefited low-income working households. Although households in the bottom 20% of the income distribution (whose average income is $15,728) receive only 5% of total family income, they received 35% of the benefits from the minimum wage increase.

* Four different tests of the two increases’ employment impact — applied to a large number of demographic groups whose wages are sensitive to the minimum wage — fail to find any systematic, significant job loss associated with the 1996-97 increases. Not only are the estimated employment effects generally economically small and statistically insignificant, they are also almost as likely to be positive as negative."

Monday, May 25, 2015

Pragmatism to Enlightened Self-Interest (post 26)

Pragmatism is a essentially an ideology concerning truth. It states that truth exists but we can never know with certainty what it is. The best we can do is move closer to it by developing theories and models and then evaluating their accuracy through the testing and tracking of their predictions.

While pragmatism is mainly about truth, there is an extension to morality which states that while we can be wrong about what is and isn't moral, we move closer to a "true" morality as we evaluate and synthesize various moral systems over time.

The evaluation of factual outcomes at the societal scale, an extremely contentious endeveour, is far less controversial than the evaluation of moral outcomes. Those involved with such evaluations use terms such as happiness, wellbeing, justice - all difficult to define and more difficult to measure. A pragmatic approach to these difficulties is to admit they exist and to continue to work to mitigate them. We are fortunate that there are so many people and organizations doing exactly this. Happiness studies have exploded over the past few decades. We can thank the efforts of psychologists and economists involved with both the Positive Psychology movement and Happiness Economics such as Martin Seligman, Daniel Gilbert, Richard Layard and Daniel Kahneman, and we can also thank their critics such as Kirk Scheider, Barbara Ehrenreich, William Davies and Barbara Held. Measuring social justice is more explicitly political and not nearly as high profile, but there are many interesting efforts - mostly concerned with the impact of philathropy and social entreprenuership. Such efforts include those by The Center for Effective Philanthropy, The Open Philanthropy Project, The Social Inclusion Monitor, The Peace and Collaborative Development Network, The DME for Peace, and The Ashoka Network.

The data amassed by such individuals and organizations is yet ambiguous, contradictory and subject to diverse, self-serving interpretations. For the purpose of changing policy or cultural ethics, this body of data is akin to religious scripture - it can used to justify just about any doctrine imaginable. Nevertheless, as long as these efforts can, for the most part, evade conscription by hegemonic powers, then the ongoing amalgamation of data and the scientific process should lead to a clearing of ambiguity and a facilitating of moral concensus.

My current working hypothesis - the hypothesis at the heart of Pragmatic Ventures - is that the eventual moral consensus these efforts are leading to is in line with the doctrine of enlightened self-interest.

That is, people are able to do the most - both for their own sense of wellbeing and for social justice within their society - when they are able to see themselves as connected to others, their fates as entwinned, and by working for their own wellbeing and justice via working for wellbeing and justice for all.

While pragmatism is mainly about truth, there is an extension to morality which states that while we can be wrong about what is and isn't moral, we move closer to a "true" morality as we evaluate and synthesize various moral systems over time.

The evaluation of factual outcomes at the societal scale, an extremely contentious endeveour, is far less controversial than the evaluation of moral outcomes. Those involved with such evaluations use terms such as happiness, wellbeing, justice - all difficult to define and more difficult to measure. A pragmatic approach to these difficulties is to admit they exist and to continue to work to mitigate them. We are fortunate that there are so many people and organizations doing exactly this. Happiness studies have exploded over the past few decades. We can thank the efforts of psychologists and economists involved with both the Positive Psychology movement and Happiness Economics such as Martin Seligman, Daniel Gilbert, Richard Layard and Daniel Kahneman, and we can also thank their critics such as Kirk Scheider, Barbara Ehrenreich, William Davies and Barbara Held. Measuring social justice is more explicitly political and not nearly as high profile, but there are many interesting efforts - mostly concerned with the impact of philathropy and social entreprenuership. Such efforts include those by The Center for Effective Philanthropy, The Open Philanthropy Project, The Social Inclusion Monitor, The Peace and Collaborative Development Network, The DME for Peace, and The Ashoka Network.

The data amassed by such individuals and organizations is yet ambiguous, contradictory and subject to diverse, self-serving interpretations. For the purpose of changing policy or cultural ethics, this body of data is akin to religious scripture - it can used to justify just about any doctrine imaginable. Nevertheless, as long as these efforts can, for the most part, evade conscription by hegemonic powers, then the ongoing amalgamation of data and the scientific process should lead to a clearing of ambiguity and a facilitating of moral concensus.

My current working hypothesis - the hypothesis at the heart of Pragmatic Ventures - is that the eventual moral consensus these efforts are leading to is in line with the doctrine of enlightened self-interest.

That is, people are able to do the most - both for their own sense of wellbeing and for social justice within their society - when they are able to see themselves as connected to others, their fates as entwinned, and by working for their own wellbeing and justice via working for wellbeing and justice for all.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)