We value our own happiness

We value our relationships with those we love

We value bringing joy to our loved ones, and we regret bringing them pain

This simple and universal moral code helps encourage us to build and maintain loving relationships and to act for the benefit of ourselves and those we love.

When interacting with friends or family, we should attempt to act in our own and their best interest. When interacting with strangers, we should be open and inviting to the formation of friendships.

Simple.

The difficulties come when we find ourselves in competition with loved ones and/or strangers, or when strangers or loved ones are in competition with each other.

When such situations occur, as they often and inevitably do, what is the optimal way to respond? When, if ever, is it appropriate to resort to violence? (and by violence I am being general - including verbal or physical attacks on or theft of someone's person, character, ideas, property, etc.).

This is perhaps the most important question in the world.

In attempting to answer it, it may be useful to distinguish the violence that stems from utility (violence as a mean to some other end) and the violence that stems from malice (violence for the sake of itself).

Let's take the alarmingly common example of one child bullying another on a playground. If I put myself in the shoes of the bully, what could be my reasons for initiating this violence? It might be because I want the other child's lunch or toy, or because it will make me more popular with the other children, or because he bullied me before and I want to stop him from trying it again, or because I just enjoy watching him suffer.

The first three reasons are out of utility - there is something to be gained from the bullying - a material object, status, security. The fourth is due to malice. It is cruelty in its most pure form - taking enjoyment from watching someone else suffer.

I think we can add to our list of universal morals the belief that violence due to malice is wrong.

This points back to something I was attempting to explain a couple of posts ago, and that is that we are more likely to act out of malice whenever we believe that others are evil. It is, so often, our belief in the evilness of another that feeds the malice within ourselves.

Putting the issue of malice aside, we still have the question of when or whether there can be justification for violence out of utility. And I think here there is, again, a near universally accepted conclusion:

Violence (without malice) is justifiable whenever the benefit outweighs the harm.

This is perhaps not so helpful, as it just shifts the question to how do we properly weigh the benefit and harm? Philosophers have been wrestling with this for centuries. I do not have an answer, but I have an observation.

When calculating the effects of violence, it is human nature to put a premium on the joy and pain of those we are closest to, while discounting the feelings of strangers. We all do it, but some do it to greater or lesser extents.

Over time, as the world has become more and more interconnected, the degree to which a stranger's pain can detract from our own happiness has increased.

Thousands of years ago it may have been possible for a member of one clan to slay a member of a distant clan and be completely insulated, in terms of human connections, from the misery such a slaying may have caused. The killer could return to his people and rejoice in their company without fear of any of them having ties of affection with the victim or the victim's loved ones.

Today such insulation is impossible. They say that through six or seven chains of relationships, we are connected to every human being on Earth.

If it is universally true that we suffer when our loved ones suffer, then - even if I harm a complete stranger in a foreign country - the harm I incur upon him will pass to those who love him, and then to those who love them, and so on until, within a handful of connections, it has returned to my loved ones, and thus to me.

Friday, February 25, 2011

Thursday, February 24, 2011

Beyond the Fall of Unions (the rise of communities?) (post 10)

I have little sympathy for the current plight of labor unions in the United States.

And that is not because I deny or do not know how important they have been in making this country great.

Anyone who studies US History and thinks we would have been better off without unions has chosen ideology over evidence (a choice far too many make - and a trend this blog tries to reverse).

The rise of unions in the United States led to the creation of safe working conditions and livable wages for millions of Americans who were previously (and who otherwise would have continued) living in poverty while working under oppressive and dangerous conditions. Our unions are one of the primary reasons the United States had such a large and strong middle class throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

But the world changed, and, for a variety of reasons, our unions did not adapt. They became too big, too corrupt and too susceptible to the claim that they impeded the freedom and competitiveness of both employers and employees. They lost a massive PR war, and that isn't because they didn't spend enough or put enough effort into it. It is because their message did not resonate with the public - while the message of Republican union busters did.

And here I must make a relevant side note:

------------------------------------------

Last week Teal and I were attempting to watch television (something we suck at) and settled on "The Last Samurai" - the epic 2003 Tom Cruise flick. In that movie, Ken Watanabe plays a rebel daimyo who is fighting to preserve the decaying Bushido culture from the Japanese bureaucrats who want to westernize the country. He fails, but even though you know he is going to fail, you are suppose to root for him and believe that his cause is noble and that he "should" have won.

I was vocally critical of this sentiment (to Teal's annoyance - part of the reason we struggle to watch TV together). One conclusion I have come to - part of my pragmatism - is that the world doesn't make mistakes. Whenever a battle is fought and one side wins, they win because they are suppose to win - because that is the only way the world can go forward. That is not to say that the winners are "better" than their opponents from an ethical standpoint. Often they are not. But even if a cruel and ruthless group comes and conquers a kind and gentle group - that conquest is necessary. It is necessary because those kind and gentle people, despite their goodness, were not able to generate enough power to protect their way of life from those who would take it from them.

In this world, it is not enough to merely be "good". You must be able to defend yourself and to adapt to changing circumstances.

----------------------

And so as I witness the Wisconsin congressmen returning to their capitol to participate in a vote that will almost certainly not go their way - I am reminded of Ken Watanabe in "The Last Samurai" and his army as they rode, wielding their katanas, into the face of machine gun fire and got mowed down.

There will always be a place for unions in this country, but after the events of the next several months their significance will be greatly reduced - and they will never return to their time of glory.

The question becomes, what, if anything, can replace the role of unions as a force protecting the rights of workers and strengthening the middle class?

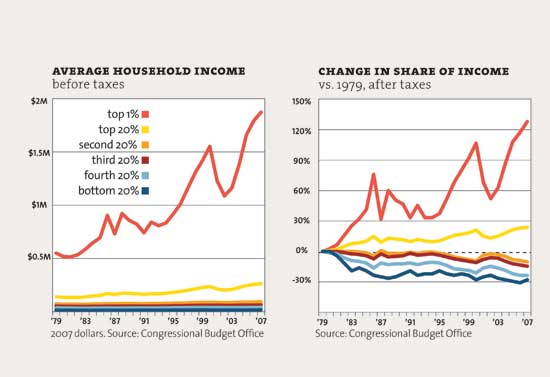

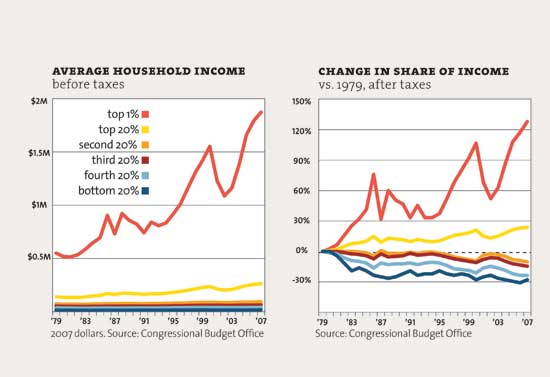

Over the past few decades, unions weren't doing a very good job. Today, unemployment is high, tens of millions of citizens are without health insurance, home ownership is declining, wealth is polarizing and much of what was once the middle class is starting to realize they are now the lower class.

I have posted similar graphics before - but let me attempt to explain what this means:

Let's say you are a middle aged, middle class person with a house, two cars and a few kids. You and your spouse combine to make somewhere between $100,000 and $200,000 per year. You have student loans, a mortgage, maybe a car payment, term life insurance, a couple of 529 plans for your kids, and a couple of underfunded IRA's or 401(k)'s. You feel like you are doing well - and you may be. But even if you are able to pay off all your debt and catch up your IRA's to generate enough for your retirement, you will very likely have little, if anything, to leave your children when you shuffle off. And maybe that is OK, but here's the problem:

If the current rate of wealth polarization continues, how are your kids going to avoid falling into the lower class?

The middle class is currently about 20% of the country. If the current polarization continues, in 30 years it will be nonexistent. There will just be the top 1% - the elite - and then a very large underclass. If your children are to avoid being in the underclass, they will have to make the leap into the elite - which means they will have to out-compete everyone who is trying to do the same thing. What are their chances of succeeding? I know you all think your kids are the smartest, most beautiful children in the world. But are they really smarter, more ambitious, more confident and popular than 99% of their peers? If not, they may be in trouble.

A couple of posts ago I explained how a new era of automation may soon lead to the evaporation of greater and greater numbers of jobs. In 30 years, how many jobs will be left that will allow someone to make today's equivalent of $50,000 to $100,000 a year? Not a lot.

The only solution to this crisis that I can see is to start reversing the trend of wealth polarization. And the best way I can think of to do that is for greater numbers of people in this country to share ownership in the companies that reap profits from automated production.

The demise of the unions is due to their failure to see workers as anything but workers. They spent too much energy fighting for higher pay, more benefits, more security and more vacations, and not enough energy fighting for employee ownership of the companies for which they worked.

The salvation of this country, if there is a salvation, lies in the increased distribution of ownership in the companies that produce our wealth. Instead of coming together to fight for benefits, vacations and higher pay - i.e. handouts - people should be coming together to fight for shared ownership.

And, as I alluded to a couple of posts ago, one way we might do this is through the formation of tight-knit communities that pool resources to invest in companies.

And that is not because I deny or do not know how important they have been in making this country great.

Anyone who studies US History and thinks we would have been better off without unions has chosen ideology over evidence (a choice far too many make - and a trend this blog tries to reverse).

The rise of unions in the United States led to the creation of safe working conditions and livable wages for millions of Americans who were previously (and who otherwise would have continued) living in poverty while working under oppressive and dangerous conditions. Our unions are one of the primary reasons the United States had such a large and strong middle class throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

But the world changed, and, for a variety of reasons, our unions did not adapt. They became too big, too corrupt and too susceptible to the claim that they impeded the freedom and competitiveness of both employers and employees. They lost a massive PR war, and that isn't because they didn't spend enough or put enough effort into it. It is because their message did not resonate with the public - while the message of Republican union busters did.

And here I must make a relevant side note:

------------------------------------------

Last week Teal and I were attempting to watch television (something we suck at) and settled on "The Last Samurai" - the epic 2003 Tom Cruise flick. In that movie, Ken Watanabe plays a rebel daimyo who is fighting to preserve the decaying Bushido culture from the Japanese bureaucrats who want to westernize the country. He fails, but even though you know he is going to fail, you are suppose to root for him and believe that his cause is noble and that he "should" have won.

I was vocally critical of this sentiment (to Teal's annoyance - part of the reason we struggle to watch TV together). One conclusion I have come to - part of my pragmatism - is that the world doesn't make mistakes. Whenever a battle is fought and one side wins, they win because they are suppose to win - because that is the only way the world can go forward. That is not to say that the winners are "better" than their opponents from an ethical standpoint. Often they are not. But even if a cruel and ruthless group comes and conquers a kind and gentle group - that conquest is necessary. It is necessary because those kind and gentle people, despite their goodness, were not able to generate enough power to protect their way of life from those who would take it from them.

In this world, it is not enough to merely be "good". You must be able to defend yourself and to adapt to changing circumstances.

----------------------

And so as I witness the Wisconsin congressmen returning to their capitol to participate in a vote that will almost certainly not go their way - I am reminded of Ken Watanabe in "The Last Samurai" and his army as they rode, wielding their katanas, into the face of machine gun fire and got mowed down.

There will always be a place for unions in this country, but after the events of the next several months their significance will be greatly reduced - and they will never return to their time of glory.

The question becomes, what, if anything, can replace the role of unions as a force protecting the rights of workers and strengthening the middle class?

Over the past few decades, unions weren't doing a very good job. Today, unemployment is high, tens of millions of citizens are without health insurance, home ownership is declining, wealth is polarizing and much of what was once the middle class is starting to realize they are now the lower class.

I have posted similar graphics before - but let me attempt to explain what this means:

Let's say you are a middle aged, middle class person with a house, two cars and a few kids. You and your spouse combine to make somewhere between $100,000 and $200,000 per year. You have student loans, a mortgage, maybe a car payment, term life insurance, a couple of 529 plans for your kids, and a couple of underfunded IRA's or 401(k)'s. You feel like you are doing well - and you may be. But even if you are able to pay off all your debt and catch up your IRA's to generate enough for your retirement, you will very likely have little, if anything, to leave your children when you shuffle off. And maybe that is OK, but here's the problem:

If the current rate of wealth polarization continues, how are your kids going to avoid falling into the lower class?

The middle class is currently about 20% of the country. If the current polarization continues, in 30 years it will be nonexistent. There will just be the top 1% - the elite - and then a very large underclass. If your children are to avoid being in the underclass, they will have to make the leap into the elite - which means they will have to out-compete everyone who is trying to do the same thing. What are their chances of succeeding? I know you all think your kids are the smartest, most beautiful children in the world. But are they really smarter, more ambitious, more confident and popular than 99% of their peers? If not, they may be in trouble.

A couple of posts ago I explained how a new era of automation may soon lead to the evaporation of greater and greater numbers of jobs. In 30 years, how many jobs will be left that will allow someone to make today's equivalent of $50,000 to $100,000 a year? Not a lot.

The only solution to this crisis that I can see is to start reversing the trend of wealth polarization. And the best way I can think of to do that is for greater numbers of people in this country to share ownership in the companies that reap profits from automated production.

The demise of the unions is due to their failure to see workers as anything but workers. They spent too much energy fighting for higher pay, more benefits, more security and more vacations, and not enough energy fighting for employee ownership of the companies for which they worked.

The salvation of this country, if there is a salvation, lies in the increased distribution of ownership in the companies that produce our wealth. Instead of coming together to fight for benefits, vacations and higher pay - i.e. handouts - people should be coming together to fight for shared ownership.

And, as I alluded to a couple of posts ago, one way we might do this is through the formation of tight-knit communities that pool resources to invest in companies.

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

The Belief in Evil (post 9)

I have hypothesized that almost all people share the same fundamental values.

1) We value our own happiness.

2) We value creating and maintaining loving relationships with others.

3) We value bringing happiness and easing pain for those we love.

Certainly, there are monsters in this world who do not share these values - psychopaths and sociopaths. Fortunately, such people are rare.

More worrisome are all of those who share these fundamental values but still act in hateful and cruel ways to strangers and even to people they love. And that describes a lot of us - including me.

So what is it that causes good people with these same core values to hate and want to hurt each other?

First, in an attempt to answer this question, let us distinguish it from a related but different question:

What is it that allows one person, who does not hate or desire to hurt others, to do something hurtful to another?

This question is easy to answer, and it does not violate any of the core values listed. It is for the gain of resources. Most animals engage in intraspecific aggression over resources. Males will injury each other in competition for females. Rival groups will kill one another in battles over foraging areas.

Whether or not such actions are accompanied with hatred or a desire to injure is impossible to say. But in our own lives we can think of many instances where we are willing to injure others without any hatred for them.

A thief may take someone's wallet without any ill will for their victim - they just need or want the money. A military commander may order a detonation that will kill noncombatants and feel terrible about it. But he does it anyway because he believes it is the best way to meet his objective. A business owner may fire a long time employee and friend. She may not want to, but she does it because she believes it will help the business survive.

We all make these sorts of calculations and take actions that we know are going to hurt strangers or even friends. We can recognize these sorts of actions because they are accompanied with guilt and/or rationalizing.

Unfortunately, if we engage in this sort of activity frequently enough, if we have a low tolerance for guilt, or if those we have injured retaliate - the guilt may turn to hatred. We stop feeling guilty and instead feel disdain. Eventually, we can convince ourselves that those we injure are evil and deserve what they are get. At that point, we may enjoy hurting them and seek to do it solely for sake of doing it.

That is one way, and perhaps the most common way, it can happen. It can also happen whenever we feel like we are the victim, or if we empathize with the victim, of a perceived injustice. Regardless of whether the perpetrator meant or wanted to hurt anyone, we may come to label that perpetrator as evil. And then we may enjoy devising and implementing an ongoing and unrelenting vengeance.

Either way, the path toward hating and wanting to hurt others opens whenever and wherever we start believing those others are evil.

It is the belief in evil that is the prime perpetuator of hatred and intentionally hurtful behavior.

1) We value our own happiness.

2) We value creating and maintaining loving relationships with others.

3) We value bringing happiness and easing pain for those we love.

Certainly, there are monsters in this world who do not share these values - psychopaths and sociopaths. Fortunately, such people are rare.

More worrisome are all of those who share these fundamental values but still act in hateful and cruel ways to strangers and even to people they love. And that describes a lot of us - including me.

So what is it that causes good people with these same core values to hate and want to hurt each other?

First, in an attempt to answer this question, let us distinguish it from a related but different question:

What is it that allows one person, who does not hate or desire to hurt others, to do something hurtful to another?

This question is easy to answer, and it does not violate any of the core values listed. It is for the gain of resources. Most animals engage in intraspecific aggression over resources. Males will injury each other in competition for females. Rival groups will kill one another in battles over foraging areas.

Whether or not such actions are accompanied with hatred or a desire to injure is impossible to say. But in our own lives we can think of many instances where we are willing to injure others without any hatred for them.

A thief may take someone's wallet without any ill will for their victim - they just need or want the money. A military commander may order a detonation that will kill noncombatants and feel terrible about it. But he does it anyway because he believes it is the best way to meet his objective. A business owner may fire a long time employee and friend. She may not want to, but she does it because she believes it will help the business survive.

We all make these sorts of calculations and take actions that we know are going to hurt strangers or even friends. We can recognize these sorts of actions because they are accompanied with guilt and/or rationalizing.

Unfortunately, if we engage in this sort of activity frequently enough, if we have a low tolerance for guilt, or if those we have injured retaliate - the guilt may turn to hatred. We stop feeling guilty and instead feel disdain. Eventually, we can convince ourselves that those we injure are evil and deserve what they are get. At that point, we may enjoy hurting them and seek to do it solely for sake of doing it.

That is one way, and perhaps the most common way, it can happen. It can also happen whenever we feel like we are the victim, or if we empathize with the victim, of a perceived injustice. Regardless of whether the perpetrator meant or wanted to hurt anyone, we may come to label that perpetrator as evil. And then we may enjoy devising and implementing an ongoing and unrelenting vengeance.

Either way, the path toward hating and wanting to hurt others opens whenever and wherever we start believing those others are evil.

It is the belief in evil that is the prime perpetuator of hatred and intentionally hurtful behavior.

Monday, February 21, 2011

The Owners of the Machines (post 8)

At the beginning of the 20th Century, when long term effects of the industrial revolution were coming into focus, prominent philosophers and economists such as Bertrand Russell and John Maynard Keynes hypothesized that increases in the automation of labor would lead to corresponding increases in the amount of leisure time for the average citizen.

How profoundly wrong they were!

In fact, just the opposite occurred. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the number of hours worked (including eduction and domestic tasks), per week, for the average family, has significantly increased. Exact amounts are difficult to pin down and greatly depend on what gets counted as work. If you do not count time spent in school or studying, some argue that, over a lifetime, we work less now than ever before - but to not count education as work (thus counting it as leisure) makes no sense. See this article on working time for further discussion.

If we count education as work, the number of hours worked per week per family has increased steadily over the past several centuries. Even in countries such as France and Sweden - countries Americans tend to view as having short work weeks and loads of leisure time - the percentage of time spent working has significantly increased. The increase has been more drastic in America, and downright brutal in countries such as China, Korea and Japan.

How has this happened? How is it that as both productivity and automation increased, the number of hours we have for leisure has decreased? It has happened because the rise of automation did not simply allow workers to do their jobs more quickly or easily. It eliminated their jobs - and thus forced them to compete for new jobs. The heightened competition for fewer and fewer jobs drove more and more people to work longer and longer in order to prove their worth.

Did anyone benefit from this? Well, yes. According to one argument, we have all benefited from it. Although we have less time for leisure than did our ancestors, arguably the time we spend working is more leisurely - as many of the more dangerous/difficult/monotonous tasks our ancestors performed have been automated or made easier by machines. And our basic needs can be met more cheaply than ever before - so that even if one is unemployed, one can (usually) gain access to food and shelter. (See The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, by Robert Fogel for an interesting take on this.)

Before the industrial revolution, large percentages of Americans experienced hunger for significant periods of time. Today, in this country, true hunger (the routine experience of being without food for days at a time) is almost nonexistent. Hunger advocates will say that 7% of Americans go hungry, but they are equating hunger with food insecurity. In America, many people who get counted as "food insecure" are obese.

So, there is an argument that, despite a net loss of leisure time and increased unemployment and underemployment, the average citizen has experienced some benefit from the automation of labor. However, the true beneficiaries of automation are, of course, the owners of the machines. Increased automation has allowed these people to drastically increase their profitability even while laying off greater and greater percentages of their employees. This trend has been accelerating over the past several decades so that currently 1% of Americans own almost 2/3rds of all the wealth of the United States.

(Go here for the source of this image)

Unfortunately, this polarization will most likely continue.

A couple of posts ago I mentioned that it will probably be a very long time (as in many generations) before we have fully autonomous robotic soldiers or a computer capable of passing the Turing Test.

However, anyone who has been following the Watson story knows that computers like Watson hold the promise, in the near-term, for a new echelon of automation in our work-force. Such computers, with just modest improvements, may become capable of doing jobs currently done by:

Cashiers

Customer Service Representatives

Translators

Copy Editors

Technical Writers

Architects

Teachers (Technical Instruction)

Doctors (Diagnostic Screening/Writing Prescriptions/Radiology)

Pharmacists

Paralegals

Lawyers (Discovery/Taking Depositions)

And probably much more.

This has to be scary for anyone currently insecure about their job or wondering what sort of jobs may be available to their children.

On the bright side, even as automation continues to eliminate jobs in this country, certain jobs will remain. People will continue to need engineers and technicians. We will also need business administrators and managers to coordinate activities between companies and subcontractors. We will still need salespeople and marketing personnel to figure out how to get people to buy our products. We will continue to need top level lawyers, judges and politicians to argue with each other over the rules of our society and the administration of justice. And we will always need medical, emergency, peacekeeping and construction personnel to respond to crises and to fix people and infrastructure when they break.

However, even though these jobs will continue to exist, they will not necessarily expand, and there will be greater and greater portions of our population competing to hold them (try asking a lawyer about whether there are too many lawyers).

In light of all of this, positively the best thing one could do to secure their financial future is to become an owner of automated production.

Can't afford to buy or start your own company right now? I suggest finding or gathering a tight-knit group of people who share fundamental values and trust each other (i.e. a community) and then pooling your resources until you have the capital to make it happen.

In the automated future towards which we are headed, there will be a sharp divide between the owners of the machines and everybody else.

How profoundly wrong they were!

In fact, just the opposite occurred. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the number of hours worked (including eduction and domestic tasks), per week, for the average family, has significantly increased. Exact amounts are difficult to pin down and greatly depend on what gets counted as work. If you do not count time spent in school or studying, some argue that, over a lifetime, we work less now than ever before - but to not count education as work (thus counting it as leisure) makes no sense. See this article on working time for further discussion.

If we count education as work, the number of hours worked per week per family has increased steadily over the past several centuries. Even in countries such as France and Sweden - countries Americans tend to view as having short work weeks and loads of leisure time - the percentage of time spent working has significantly increased. The increase has been more drastic in America, and downright brutal in countries such as China, Korea and Japan.

How has this happened? How is it that as both productivity and automation increased, the number of hours we have for leisure has decreased? It has happened because the rise of automation did not simply allow workers to do their jobs more quickly or easily. It eliminated their jobs - and thus forced them to compete for new jobs. The heightened competition for fewer and fewer jobs drove more and more people to work longer and longer in order to prove their worth.

Did anyone benefit from this? Well, yes. According to one argument, we have all benefited from it. Although we have less time for leisure than did our ancestors, arguably the time we spend working is more leisurely - as many of the more dangerous/difficult/monotonous tasks our ancestors performed have been automated or made easier by machines. And our basic needs can be met more cheaply than ever before - so that even if one is unemployed, one can (usually) gain access to food and shelter. (See The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, by Robert Fogel for an interesting take on this.)

Before the industrial revolution, large percentages of Americans experienced hunger for significant periods of time. Today, in this country, true hunger (the routine experience of being without food for days at a time) is almost nonexistent. Hunger advocates will say that 7% of Americans go hungry, but they are equating hunger with food insecurity. In America, many people who get counted as "food insecure" are obese.

So, there is an argument that, despite a net loss of leisure time and increased unemployment and underemployment, the average citizen has experienced some benefit from the automation of labor. However, the true beneficiaries of automation are, of course, the owners of the machines. Increased automation has allowed these people to drastically increase their profitability even while laying off greater and greater percentages of their employees. This trend has been accelerating over the past several decades so that currently 1% of Americans own almost 2/3rds of all the wealth of the United States.

(Go here for the source of this image)

Unfortunately, this polarization will most likely continue.

A couple of posts ago I mentioned that it will probably be a very long time (as in many generations) before we have fully autonomous robotic soldiers or a computer capable of passing the Turing Test.

However, anyone who has been following the Watson story knows that computers like Watson hold the promise, in the near-term, for a new echelon of automation in our work-force. Such computers, with just modest improvements, may become capable of doing jobs currently done by:

Cashiers

Customer Service Representatives

Translators

Copy Editors

Technical Writers

Architects

Teachers (Technical Instruction)

Doctors (Diagnostic Screening/Writing Prescriptions/Radiology)

Pharmacists

Paralegals

Lawyers (Discovery/Taking Depositions)

And probably much more.

This has to be scary for anyone currently insecure about their job or wondering what sort of jobs may be available to their children.

On the bright side, even as automation continues to eliminate jobs in this country, certain jobs will remain. People will continue to need engineers and technicians. We will also need business administrators and managers to coordinate activities between companies and subcontractors. We will still need salespeople and marketing personnel to figure out how to get people to buy our products. We will continue to need top level lawyers, judges and politicians to argue with each other over the rules of our society and the administration of justice. And we will always need medical, emergency, peacekeeping and construction personnel to respond to crises and to fix people and infrastructure when they break.

However, even though these jobs will continue to exist, they will not necessarily expand, and there will be greater and greater portions of our population competing to hold them (try asking a lawyer about whether there are too many lawyers).

In light of all of this, positively the best thing one could do to secure their financial future is to become an owner of automated production.

Can't afford to buy or start your own company right now? I suggest finding or gathering a tight-knit group of people who share fundamental values and trust each other (i.e. a community) and then pooling your resources until you have the capital to make it happen.

In the automated future towards which we are headed, there will be a sharp divide between the owners of the machines and everybody else.

Friday, February 18, 2011

The Seductive Appeal of Loneliness (post 7)

My most fundamental values can be stated as follows:

1) I value my own happiness.

2) My happiness is dependent upon my ability to form and maintain relationships with others.

3) My happiness is strengthened when those I care about are happy and is unsettled when those I care about are in pain.

These three simple realizations give my life unambiguous purpose and direction. I know that relationships with others are the most important things in my life. I know that causing pain to those I love will inevitably cause me pain, and that bringing joy to those I love will inevitably bring me joy.

Furthermore, I believe these basic values are shared (either consciously or unconsciously) by most and that they lie at the heart of every major religion. When I claim that divergence in values is what breaks apart relationships and communities, it is not these fundamental values that are the cause. It is secondary and tertiary values that become the sources of disagreement.

Yet even for those of us who have explicitly realized the importance of these values, there are many times when we forget or disregard them. We become fixated on our pain or perceived inequities and so convinced (rightly or wrongly) that the source of such pain is other people, that we stop reaching out/cut off affection/withdraw.

As I have said before, sometimes there are very good reasons for this. Instances of domestic abuse, bullying, hate crimes, etc. are all examples. There are unfortunately many circumstances when we must defend ourselves from those who have harmed or seek to harm us.

But perhaps more unfortunate are those circumstances where people withdraw, convinced or afraid that they are or would be wronged or ignored, when there is no true ill intent.

Everyone of us knows someone who is lonely.

Many of us know several such people.

Most of us have experienced it ourselves.

And for those of us who have experienced it, we know there is something attractive about it - something noble, defiant, self-righteous, as well as comforting and very safe. There is also power in it, especially if we learn to interact with others from within the safety of a shell or affected persona. We can then appear to be social and can more easily deceive and manipulate others and obtain substitutes for the joy we no longer experience from authentic relationships.

But the loneliness is still there, and despite its comfort, safety and dignity - despite whatever substances it may furnish for gaining pleasure - it is a prison.

1) I value my own happiness.

2) My happiness is dependent upon my ability to form and maintain relationships with others.

3) My happiness is strengthened when those I care about are happy and is unsettled when those I care about are in pain.

These three simple realizations give my life unambiguous purpose and direction. I know that relationships with others are the most important things in my life. I know that causing pain to those I love will inevitably cause me pain, and that bringing joy to those I love will inevitably bring me joy.

Furthermore, I believe these basic values are shared (either consciously or unconsciously) by most and that they lie at the heart of every major religion. When I claim that divergence in values is what breaks apart relationships and communities, it is not these fundamental values that are the cause. It is secondary and tertiary values that become the sources of disagreement.

Yet even for those of us who have explicitly realized the importance of these values, there are many times when we forget or disregard them. We become fixated on our pain or perceived inequities and so convinced (rightly or wrongly) that the source of such pain is other people, that we stop reaching out/cut off affection/withdraw.

As I have said before, sometimes there are very good reasons for this. Instances of domestic abuse, bullying, hate crimes, etc. are all examples. There are unfortunately many circumstances when we must defend ourselves from those who have harmed or seek to harm us.

But perhaps more unfortunate are those circumstances where people withdraw, convinced or afraid that they are or would be wronged or ignored, when there is no true ill intent.

Everyone of us knows someone who is lonely.

Many of us know several such people.

Most of us have experienced it ourselves.

And for those of us who have experienced it, we know there is something attractive about it - something noble, defiant, self-righteous, as well as comforting and very safe. There is also power in it, especially if we learn to interact with others from within the safety of a shell or affected persona. We can then appear to be social and can more easily deceive and manipulate others and obtain substitutes for the joy we no longer experience from authentic relationships.

But the loneliness is still there, and despite its comfort, safety and dignity - despite whatever substances it may furnish for gaining pleasure - it is a prison.

Thursday, February 17, 2011

The Eye of Watson Turns Red? (post 6)

Congratulations to Watson!

His victory is a major milestone for achievement in computing.

One of the first computer programs I wrote was a program to solve sudoku puzzles. I wrote it in scheme while finishing my math degree at IU. It was shortly after that I decided to stop doing sudoku and return to crossword puzzles. I figured that if I could write a program to solve them, then sudoku couldn't be that cognitively challenging. I could not begin to imagine how to write a program to solve crosswords. I told myself that if anyone ever did, I would be deeply impressed. That was in 2004 - turns out such a program had been written in 1999 - but it used the internet, so that's cheating (typing in a crossword clue into google can almost immediately get you the answer). I still don't know if a crossword solver has been written that does not use the internet, but I think Watson's achievement would trump that (and no, Watson did not use the internet).

To my mind, the most impressive aspect of what Watson did was the interpreting of the clues to form relevant search strategies. That demonstrates an advanced degree of language understanding.

Computer scientists long ago realized that the most difficult cognitive task we perform is holding conversations with other intelligence beings. It was Alan Turing (a personal hero of mine) who declared the ultimate challenge for a programmer is to design a machine capable of conversing with a human without the human realizing that she is talking to a machine. This is known as the Turing Test - and it has never been passed in a meaningful way. Even Watson, who can so elegantly say, "What is shoe?" could not talk to you for any significant period of time without you realizing that something was weird ("Why do you keep asking questions? Stop it!").

It is inevitable that the Turing Test will be passed; it is only a matter of when. We have been notoriously bad at predicting the speed (and order) in which computing milestones would be reached. Purportedly, Marvin Minsky, the former head of the AI program at MIT, told DARPA in the 60's that he could produce fully autonomous robotic soldiers within ten years (see McCorduck, Pamela (2004), Machines Who Think) They're still waiting.

For now, it seems safe to say that it isn't going to happen soon, and it is and will continue to be the internet - and its ability to help us to converse with one another - that remains the most compelling and inspiring technological achievement of our era.

Oh, and no, the eye of Watson did not turn red. We are safe.

But watch this...

His victory is a major milestone for achievement in computing.

One of the first computer programs I wrote was a program to solve sudoku puzzles. I wrote it in scheme while finishing my math degree at IU. It was shortly after that I decided to stop doing sudoku and return to crossword puzzles. I figured that if I could write a program to solve them, then sudoku couldn't be that cognitively challenging. I could not begin to imagine how to write a program to solve crosswords. I told myself that if anyone ever did, I would be deeply impressed. That was in 2004 - turns out such a program had been written in 1999 - but it used the internet, so that's cheating (typing in a crossword clue into google can almost immediately get you the answer). I still don't know if a crossword solver has been written that does not use the internet, but I think Watson's achievement would trump that (and no, Watson did not use the internet).

To my mind, the most impressive aspect of what Watson did was the interpreting of the clues to form relevant search strategies. That demonstrates an advanced degree of language understanding.

Computer scientists long ago realized that the most difficult cognitive task we perform is holding conversations with other intelligence beings. It was Alan Turing (a personal hero of mine) who declared the ultimate challenge for a programmer is to design a machine capable of conversing with a human without the human realizing that she is talking to a machine. This is known as the Turing Test - and it has never been passed in a meaningful way. Even Watson, who can so elegantly say, "What is shoe?" could not talk to you for any significant period of time without you realizing that something was weird ("Why do you keep asking questions? Stop it!").

It is inevitable that the Turing Test will be passed; it is only a matter of when. We have been notoriously bad at predicting the speed (and order) in which computing milestones would be reached. Purportedly, Marvin Minsky, the former head of the AI program at MIT, told DARPA in the 60's that he could produce fully autonomous robotic soldiers within ten years (see McCorduck, Pamela (2004), Machines Who Think) They're still waiting.

For now, it seems safe to say that it isn't going to happen soon, and it is and will continue to be the internet - and its ability to help us to converse with one another - that remains the most compelling and inspiring technological achievement of our era.

Oh, and no, the eye of Watson did not turn red. We are safe.

But watch this...

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

Sharing Values (post 5)

It has become my conclusion that the things that bind people together in relationships and communities are:

1) Shared knowledge (experiences/memories)

2) Shared values (preferences/morals/ethics)

Of these, shared values are more important. When we think about who we want to spend our time with, we most often look to those who share certain preferences and values (perhaps right after considering how cute and/or funny they are...).

Not all values carry the same weight. The most important we call morals. We see how people's behavior changes when certain preferences (like being kind to animals) rise in importance to the level of morals (joining PETA and throwing red paint at people).

It is shared and unshared morality that is most prominent in making and breaking communities.

One might see that as a cause for concern - as something that would forever limit who we could or could not form communities with. Luckily, it is my optimistic belief that most of us share morality to a much greater extent than at first glance we might ever believe. I think that for most of us (with some important exceptions), if we were to truly get to know each other, regardless of religion or culture, we would find that our most important values - our core ethics - are very similar.

To test this optimism, and to further my goal of promoting the formation of relationships and communities, I encourage people to spend some time reflecting on what their deepest and most profound values might be.

When I do this myself, I come to a couple of important conclusions.

1) I value my own happiness.

2) My happiness is dependent on the happiness of others.

I am not selfless or altruistic. I'm looking out for number one. But I've come to realize that my happiness is utterly dependent on the happiness of others. I am not an island. I cannot sit in a room full of miserable people and be perfectly content - nor would I want to hang out with anyone who could.

Realizing this, I realize that it is in my best interest to look out for, think about and care about others.

Remembering this helps to guide me in my actions and decisions - and helps me gain confidence in my values without resorting to fundamentalism. Obviously, there are a lot of situations/dilemmas where I need to make a decision that cannot be aided by this simple moral. But there are a surprising number of situations where it is helpful. Especially whenever I desire to hurt someone (which shockingly happens from time to time).

Without worrying about complicated ethical scenarios about whether it's OK to kill one person to save five, or if it's OK to lie if it's going to help someone - I think that if I could just get to the point where I never intentionally acted in an unkind or hurtful way due malice, jealously, fear or vengeance - then I think I would be doing OK.

1) Shared knowledge (experiences/memories)

2) Shared values (preferences/morals/ethics)

Of these, shared values are more important. When we think about who we want to spend our time with, we most often look to those who share certain preferences and values (perhaps right after considering how cute and/or funny they are...).

Not all values carry the same weight. The most important we call morals. We see how people's behavior changes when certain preferences (like being kind to animals) rise in importance to the level of morals (joining PETA and throwing red paint at people).

It is shared and unshared morality that is most prominent in making and breaking communities.

One might see that as a cause for concern - as something that would forever limit who we could or could not form communities with. Luckily, it is my optimistic belief that most of us share morality to a much greater extent than at first glance we might ever believe. I think that for most of us (with some important exceptions), if we were to truly get to know each other, regardless of religion or culture, we would find that our most important values - our core ethics - are very similar.

To test this optimism, and to further my goal of promoting the formation of relationships and communities, I encourage people to spend some time reflecting on what their deepest and most profound values might be.

When I do this myself, I come to a couple of important conclusions.

1) I value my own happiness.

2) My happiness is dependent on the happiness of others.

I am not selfless or altruistic. I'm looking out for number one. But I've come to realize that my happiness is utterly dependent on the happiness of others. I am not an island. I cannot sit in a room full of miserable people and be perfectly content - nor would I want to hang out with anyone who could.

Realizing this, I realize that it is in my best interest to look out for, think about and care about others.

Remembering this helps to guide me in my actions and decisions - and helps me gain confidence in my values without resorting to fundamentalism. Obviously, there are a lot of situations/dilemmas where I need to make a decision that cannot be aided by this simple moral. But there are a surprising number of situations where it is helpful. Especially whenever I desire to hurt someone (which shockingly happens from time to time).

Without worrying about complicated ethical scenarios about whether it's OK to kill one person to save five, or if it's OK to lie if it's going to help someone - I think that if I could just get to the point where I never intentionally acted in an unkind or hurtful way due malice, jealously, fear or vengeance - then I think I would be doing OK.

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

Relativism vs. Fundamentalism: The Plight of Modern Religion (post 4)

In this post I want to look closer at forces inhibiting the formation of communities and relationships.

At the micro level - the level of interpersonal relationships - it has been mentioned that our ability and desire to hurt each other (and our fear of being hurt) is a major obstacle. And to this we could add our ability to annoy, bore and infuriate each other. I think everyone has experienced the sensation of reaching out to someone, but then - once engaged in a conversation or activity - realizing that they are hurtful/boring/annoying/infuriating. And, if we limit ourselves to the micro level, we may never fully understand why this is.

At the macro level - the level of sociology - we have briefly discussed the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance - the negation emotions we feel when attempting to assimilate conflicting ideas and beliefs. It is interactions with other people that is a major cause of cognitive dissonance - and the more people we interact with, the more dissonance we may experience.

We can limit dissonance by limiting the types of conversation we engage in to those such as the weather, sports, or food or by limiting the types of people with interact with to those who already share our core beliefs and values.

This second strategy - interacting mainly with those who share our beliefs and values - has become increasingly difficult. A few hundred years ago, one might easily live in a town and go one's entire life without ever speaking with someone from a different religion or with radically different tastes or beliefs. Today, it can be difficult to find others with similar beliefs even within one's immediate family.

Travel, mass media and the internet have made information about other cultures and lifestyles immediately available to anyone with the slightest bit of curiosity. Ultimately, I believe this is a good thing - but there are some negative consequences. We often don't know what to do with all these conflicting sets of values and beliefs. It can become difficult to create and defend our own moral positions.

Often, and perhaps increasingly, people turn to one of two general solutions: relativism or fundamentalism.

In relativism we attempt to say that maybe nothing is truly right or wrong - or maybe everything is kind of right and wrong at the same time - and then we go with whatever feels right at a particular time. It does not imply hedonism (though that can be a result), but it leads to an eclectic set of values and beliefs haphazardly taken from a variety of cultures and traditions. This can be beautiful, but it makes it difficult to feel confident and secure in one's values or to instill, defend or enforce moral behavior in others. This is problematic in child-raising when relativistic parents, insecure about their beliefs, prefer to let their children make their own conclusions about what is right and wrong. It is problematic because children need rules, they need boundaries, and they need those rules and boundaries to be justified and consistent. It is also problematic because it becomes difficult to share one's beliefs and values with others, even other relativists, when there is bound to be significant amounts of disagreement. And while it is great, in theory, to believe that two people can believe in conflicting ideas and both be right - if these people are going to make important decisions that affect large groups of people - conflicting beliefs will come to a head, and relativists will need some way of advocating for their beliefs over others. In practice this leads many relativists to avoid positions of authority.

In fundamentalism we become so averse to the dissonance of relativism that we latch onto a highly regulated and traditional set of values and beliefs that asserts itself as the only true set of values and beliefs, and decries the near limitless sets of competing beliefs as false. This solution is problematic because it creates ever increasing amounts of conflict between rival groups, and because it forces its adherents to renounce ideas or facts that they otherwise would accept as true. Not only is this denial of facts difficult on the psyche, but it inevitably leads to failures when attempting to enact plans dependent on counterfactual ideas.

So how do we navigate through the bombardment of conflicting ideas and beliefs in our modern world without succumbing to the pitfalls of relativism and fundamentalism? And how do we engage in meaningful relationships and create communities with others who do not necessarily share our values? How do we construct beliefs that are authentically our own - and advocate for them with confidence and authority?

These are some of the pressing questions that this blog seeks to explore.

At the micro level - the level of interpersonal relationships - it has been mentioned that our ability and desire to hurt each other (and our fear of being hurt) is a major obstacle. And to this we could add our ability to annoy, bore and infuriate each other. I think everyone has experienced the sensation of reaching out to someone, but then - once engaged in a conversation or activity - realizing that they are hurtful/boring/annoying/infuriating. And, if we limit ourselves to the micro level, we may never fully understand why this is.

At the macro level - the level of sociology - we have briefly discussed the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance - the negation emotions we feel when attempting to assimilate conflicting ideas and beliefs. It is interactions with other people that is a major cause of cognitive dissonance - and the more people we interact with, the more dissonance we may experience.

We can limit dissonance by limiting the types of conversation we engage in to those such as the weather, sports, or food or by limiting the types of people with interact with to those who already share our core beliefs and values.

This second strategy - interacting mainly with those who share our beliefs and values - has become increasingly difficult. A few hundred years ago, one might easily live in a town and go one's entire life without ever speaking with someone from a different religion or with radically different tastes or beliefs. Today, it can be difficult to find others with similar beliefs even within one's immediate family.

Travel, mass media and the internet have made information about other cultures and lifestyles immediately available to anyone with the slightest bit of curiosity. Ultimately, I believe this is a good thing - but there are some negative consequences. We often don't know what to do with all these conflicting sets of values and beliefs. It can become difficult to create and defend our own moral positions.

Often, and perhaps increasingly, people turn to one of two general solutions: relativism or fundamentalism.

In relativism we attempt to say that maybe nothing is truly right or wrong - or maybe everything is kind of right and wrong at the same time - and then we go with whatever feels right at a particular time. It does not imply hedonism (though that can be a result), but it leads to an eclectic set of values and beliefs haphazardly taken from a variety of cultures and traditions. This can be beautiful, but it makes it difficult to feel confident and secure in one's values or to instill, defend or enforce moral behavior in others. This is problematic in child-raising when relativistic parents, insecure about their beliefs, prefer to let their children make their own conclusions about what is right and wrong. It is problematic because children need rules, they need boundaries, and they need those rules and boundaries to be justified and consistent. It is also problematic because it becomes difficult to share one's beliefs and values with others, even other relativists, when there is bound to be significant amounts of disagreement. And while it is great, in theory, to believe that two people can believe in conflicting ideas and both be right - if these people are going to make important decisions that affect large groups of people - conflicting beliefs will come to a head, and relativists will need some way of advocating for their beliefs over others. In practice this leads many relativists to avoid positions of authority.

In fundamentalism we become so averse to the dissonance of relativism that we latch onto a highly regulated and traditional set of values and beliefs that asserts itself as the only true set of values and beliefs, and decries the near limitless sets of competing beliefs as false. This solution is problematic because it creates ever increasing amounts of conflict between rival groups, and because it forces its adherents to renounce ideas or facts that they otherwise would accept as true. Not only is this denial of facts difficult on the psyche, but it inevitably leads to failures when attempting to enact plans dependent on counterfactual ideas.

So how do we navigate through the bombardment of conflicting ideas and beliefs in our modern world without succumbing to the pitfalls of relativism and fundamentalism? And how do we engage in meaningful relationships and create communities with others who do not necessarily share our values? How do we construct beliefs that are authentically our own - and advocate for them with confidence and authority?

These are some of the pressing questions that this blog seeks to explore.

Monday, February 14, 2011

The Evolution of Community (and the Internet) (post 3)

Today is a day for reaching out to those you love, and I hope everyone is able to do that.

Happy Valentine's Day.

As the last post was on relationships, this one is dedicated to the concept of community as well as ways in which the internet is changing it.

What I mean by community is what I believe everyone means by community - groups of people who all know each other and interact with one another at certain times in certain contexts.

There was once a time (tens of thousands of years ago) when all people lived together in well defined communities - groups of about 30 to 300 people who would eat, sleep, work and rest amongst each other day in and day out. Regardless of how well they liked each other, they knew each other and depended on each other. This was the rather simple social system from which we all come.

With the arise of civilization, communities became more complex - the number of communities to which people could belong became greater, and types of communities became more diverse and less well defined. This trend has continued until today where things are very complicated and where it might be easy for people to count their friends and acquaintances but difficult to identify groups who eat, rest and work with each other on a regular basis or for sustained periods of time. The most clearly defined community we have is usually the people we work with, who, if we're lucky, are counted among our friends, but are more often people we would not voluntarily associate with if given a choice. And that, I believe, is and has been a major source of discontent in the modern world - too many people spend far too much time separated from people who care for and about each other.

Why has civilization had this disruptive affect on the structures of communities? One theory is as follows. Humans are ideally suited to live in communities of about 150 people. This is known as Dunbar's number (identified by Anthropologist Robin Dunbar). When we try to exist in group sizes that are significantly larger than 150 people, cognitive dissonance and social chaos escalate. In ancient times, this would cause large groups to fracture into smaller groups and separate. However, as populations within regions increased, it became increasingly difficult for large groups to simply fracture and separate. Warfare between rival groups intensified, and groups that could figure out ways to maintain membership sizes above Dunbar's number gained an important advantage. At that point there were two opposing forces pressuring group size: psychological dissonance and social chaos pressuring large groups to fracture, and inter-group competition and the need for size advantages pressuring groups to grow larger. Civilizations were born whenever humans figured out how to overcome the dissonance and chaos created by increased group size and get larger numbers of people to live in closer proximity and work toward common goals. The need and ability to increase group size and overcome dissonance grew throughout history and accelerated during the industrial revolution and modernity.

So the sizes of top-level social entities are at all time highs, and while that gives nations like China and corporations like Walmart many competitive advantages, it wrecks havoc on the sense of community and social well-being of the people existing within these monstrosities. It is no wonder why prescriptions for anti-anxiety and anti-depression medications continue to increase at alarming rates.

And so we have a sort of Catch-22. In order to succeed in this world, we must live within social structures capable of banding together tens and hundreds of millions of people - structures that are necessarily deleterious to the formation and maintenance of authentic communities and to our psychological well-being. In order to succeed in this world, we may have to work for companies we don't necessarily like, help make or sell products we don't necessarily believe in, move our families to another town, have our children educated by strangers, or live amongst neighbors with different values, tastes and beliefs. This is not ideal. It is not how we want to live, but it is how we live, and we come to accept it even as we look for ways to make it better.

It may be that the internet - and especially social networking - affords a unique solution to our most prominent and problematic social ailments. It gives us a way to fight against the isolating and community fracturing forces of civilization. Maybe this is why so many are proclaiming that the internet is about to change us and our societies in ways far more profound and fundamental than any other social or cultural revolution in history. Over the past few weeks, two nations have used to internet to overthrow their governments. Smart phones and social networking are increasing their dominance over every aspect of our social and professional lives. We use them to find companies we want to work for, find products we believe in, stay connected to family and friends no matter where we might live, send our children to the schools of our choice, and learn a bit more about why our neighbors hold their strange values - making them seem a bit less strange.

And this is just the beginning. The internet is in its infancy. Who knows what its full potential might be.

The revolution does not need to be televised. It's free to download off the internet.

Happy Valentine's Day.

As the last post was on relationships, this one is dedicated to the concept of community as well as ways in which the internet is changing it.

What I mean by community is what I believe everyone means by community - groups of people who all know each other and interact with one another at certain times in certain contexts.

There was once a time (tens of thousands of years ago) when all people lived together in well defined communities - groups of about 30 to 300 people who would eat, sleep, work and rest amongst each other day in and day out. Regardless of how well they liked each other, they knew each other and depended on each other. This was the rather simple social system from which we all come.

With the arise of civilization, communities became more complex - the number of communities to which people could belong became greater, and types of communities became more diverse and less well defined. This trend has continued until today where things are very complicated and where it might be easy for people to count their friends and acquaintances but difficult to identify groups who eat, rest and work with each other on a regular basis or for sustained periods of time. The most clearly defined community we have is usually the people we work with, who, if we're lucky, are counted among our friends, but are more often people we would not voluntarily associate with if given a choice. And that, I believe, is and has been a major source of discontent in the modern world - too many people spend far too much time separated from people who care for and about each other.

Why has civilization had this disruptive affect on the structures of communities? One theory is as follows. Humans are ideally suited to live in communities of about 150 people. This is known as Dunbar's number (identified by Anthropologist Robin Dunbar). When we try to exist in group sizes that are significantly larger than 150 people, cognitive dissonance and social chaos escalate. In ancient times, this would cause large groups to fracture into smaller groups and separate. However, as populations within regions increased, it became increasingly difficult for large groups to simply fracture and separate. Warfare between rival groups intensified, and groups that could figure out ways to maintain membership sizes above Dunbar's number gained an important advantage. At that point there were two opposing forces pressuring group size: psychological dissonance and social chaos pressuring large groups to fracture, and inter-group competition and the need for size advantages pressuring groups to grow larger. Civilizations were born whenever humans figured out how to overcome the dissonance and chaos created by increased group size and get larger numbers of people to live in closer proximity and work toward common goals. The need and ability to increase group size and overcome dissonance grew throughout history and accelerated during the industrial revolution and modernity.

So the sizes of top-level social entities are at all time highs, and while that gives nations like China and corporations like Walmart many competitive advantages, it wrecks havoc on the sense of community and social well-being of the people existing within these monstrosities. It is no wonder why prescriptions for anti-anxiety and anti-depression medications continue to increase at alarming rates.

And so we have a sort of Catch-22. In order to succeed in this world, we must live within social structures capable of banding together tens and hundreds of millions of people - structures that are necessarily deleterious to the formation and maintenance of authentic communities and to our psychological well-being. In order to succeed in this world, we may have to work for companies we don't necessarily like, help make or sell products we don't necessarily believe in, move our families to another town, have our children educated by strangers, or live amongst neighbors with different values, tastes and beliefs. This is not ideal. It is not how we want to live, but it is how we live, and we come to accept it even as we look for ways to make it better.

It may be that the internet - and especially social networking - affords a unique solution to our most prominent and problematic social ailments. It gives us a way to fight against the isolating and community fracturing forces of civilization. Maybe this is why so many are proclaiming that the internet is about to change us and our societies in ways far more profound and fundamental than any other social or cultural revolution in history. Over the past few weeks, two nations have used to internet to overthrow their governments. Smart phones and social networking are increasing their dominance over every aspect of our social and professional lives. We use them to find companies we want to work for, find products we believe in, stay connected to family and friends no matter where we might live, send our children to the schools of our choice, and learn a bit more about why our neighbors hold their strange values - making them seem a bit less strange.

And this is just the beginning. The internet is in its infancy. Who knows what its full potential might be.

The revolution does not need to be televised. It's free to download off the internet.

Friday, February 11, 2011

Our Relationships with One Another (post 2)

Putting aside the idea that I have a big head and like the sound of my own voice (or the look of my own typeset), my reasons for writing this blog are simple.

I want to share with people my belief that it is our relationships with one another that are the most important things in our lives. Of all that we might accomplish, it is the mutual understandings with friends and family that are the most satisfying and most permanent. Those moments when two people connect with each other in meaningful ways - gain greater understanding of each other, glimpse the world through each other's eyes - those are the most beautiful moments in the universe.

We can build cities, invent new technology, draft constitutions for nations - all of which have profound effects on the future of humanity. But there would be no point or purpose to any of that if not for the simple acts of spending time with each other and enjoying each others' company.

When I write, I comment on many things. And, as my former students will gleefully confirm, I easily get sidetracked. But underlying the details and tangents, I am propelled by a desire to share myself with others - to work toward those moments of mutual understanding - and to, whenever possible, encourage others to do the same.

This is not to say that creating or maintaining meaningful relationships is easy. It is a fact that, for whatever reasons, we can be and often are very hurtful to each other. Why do we take pleasure in hurting one another? I don't know. Perhaps that is topic for another time. But we do hurt each other - and our ability and desire to hurt is the major obstacle in forming and maintaining our relationships.

I sometimes feel that I have spent too much of my life avoiding others (out of fear) than reaching out. It is something I regret but luckily can rectify. In my new job, I am forced to reach out to people all the time - and I have often sat in front of my phone with a list of numbers that I'm suppose to call and observed as my heart rate intensified and the blood drained from my face.

When I am afraid, I try to tell myself that the worst thing that can happen is pain (both physical and emotional). The question that life poses to us is whether our desire to connect with others is greater than our fear of (and tolerance for) the pain that they can (and do) cause.

Sometimes the answer is no (and rightfully so). Hopefully, more often - the answer is yes.

I want to share with people my belief that it is our relationships with one another that are the most important things in our lives. Of all that we might accomplish, it is the mutual understandings with friends and family that are the most satisfying and most permanent. Those moments when two people connect with each other in meaningful ways - gain greater understanding of each other, glimpse the world through each other's eyes - those are the most beautiful moments in the universe.

We can build cities, invent new technology, draft constitutions for nations - all of which have profound effects on the future of humanity. But there would be no point or purpose to any of that if not for the simple acts of spending time with each other and enjoying each others' company.

When I write, I comment on many things. And, as my former students will gleefully confirm, I easily get sidetracked. But underlying the details and tangents, I am propelled by a desire to share myself with others - to work toward those moments of mutual understanding - and to, whenever possible, encourage others to do the same.

This is not to say that creating or maintaining meaningful relationships is easy. It is a fact that, for whatever reasons, we can be and often are very hurtful to each other. Why do we take pleasure in hurting one another? I don't know. Perhaps that is topic for another time. But we do hurt each other - and our ability and desire to hurt is the major obstacle in forming and maintaining our relationships.

I sometimes feel that I have spent too much of my life avoiding others (out of fear) than reaching out. It is something I regret but luckily can rectify. In my new job, I am forced to reach out to people all the time - and I have often sat in front of my phone with a list of numbers that I'm suppose to call and observed as my heart rate intensified and the blood drained from my face.

When I am afraid, I try to tell myself that the worst thing that can happen is pain (both physical and emotional). The question that life poses to us is whether our desire to connect with others is greater than our fear of (and tolerance for) the pain that they can (and do) cause.

Sometimes the answer is no (and rightfully so). Hopefully, more often - the answer is yes.

Thursday, February 10, 2011

A Little About Me (post 1)

Like most of us, I enjoy commenting on life and society - and, toward that end, I have perhaps spent more than my fair share of time exploring various ideas, beliefs and ways of living.

I call myself a pragmatist because, as far as labels go, it is a close fit. It isn't perfect - but it works, and there is a pleasant irony in that :)

My desire to blog began some time after I dropped out of grad school. I was struggling with the big questions - Why do I exist? Is there a God? Is there free will? How will I pay my rent? Yadda, yadda yadda...

Since then I have done many things. Most famously, for a time, I wandered around rural America with a beard and a backpack - visiting family, friends and strange communities in stranger places (a pagan commune in the backwoods of Indiana, or a fundamentalist cult in the suburbs of Chattanooga).

Eventually I returned to school to study mathematics, and then taught math for years - in Massachusetts, and then Bloomington. Now I live and work as a financial advisor in Indianapolis. I am happily engaged, and my fiancee and I look forward to starting a family.

Throughout my adventures there was always one unifying theme: the search for integration to a fractured sense of community. And in that desire for a more complete and permanent community, I know that I was not and am not alone.

The marvels of the modern world are many, but if there is one regret, it is that we too often end up spread out over vast regions (both physical and ideological) - leaving us isolated and longing for idyllic notions of a simpler world where we could spend each day living and loving amidst close-knit friends and family.

It is no wonder that cell phones, the internet and social networking are the dominate technological achievements of our era. More than anything, they help to connect us. They help us feel less alone. And there is nothing more valuable than that.

The purpose of this blog is to attempt to understand the ways in which our world is changing - and the ways in which we can participate in these changes - so that, at the end of each day, the feeling gets a little bit stronger, that we are all in this thing together.